This episode is often described differently from one published source to the next. What follows here is my attempt to clarify the details of this event by balancing existing accounts with contemporary source material.

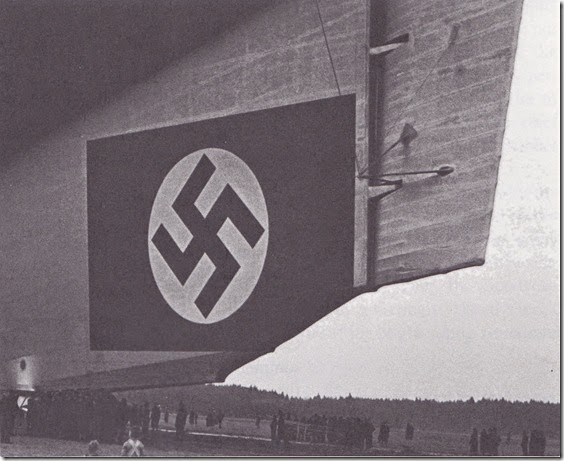

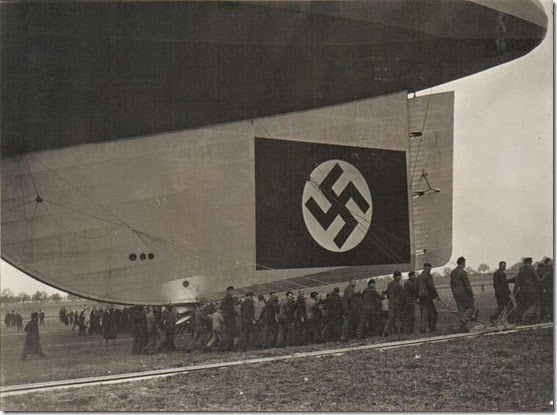

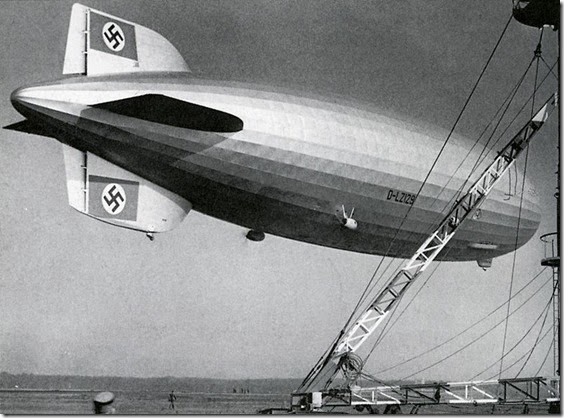

*Please note that it was impossible to show the actual fin damage without also showing a number of conspicuous swastika images. This is not intended to glorify NSDAP ideology, but is merely a matter of historical accuracy.*

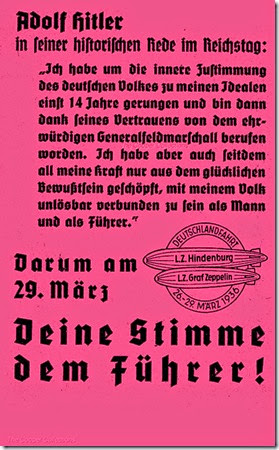

Early on the morning of March 26, 1936, the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei’s new flagship, the LZ 129 Hindenburg, prepared to depart her hanger for a four-day flight over Germany. Together with her sister ship, the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, the Hindenburg was to fly over Germany dropping leaflets and broadcasting party political messages in support of Adolf Hitler's remilitarization of the Rheinland, on which the German people would be casting a referendum vote on March 29.

It was a sign of the times, and not an entirely welcome one. In order to obtain the necessary capital to finish construction of the Hindenburg, which had begun in 1932 at the height of the Great Depression, the flight operations wing of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin had been nationalized as the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei in early 1935. Up to that point, the flights of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin’s airships had been scheduled and coordinated internally, largely under the control of Dr. Hugo Eckener, the company’s director.

Dr. Eckener’s chief operational priority, aside from the obvious goal of making the airships profitable, had always been safety. In more than a quarter century since the first DELAG sightseeing flights, not a single passenger had ever been killed or even seriously injured aboard a Zeppelin, and this was largely due to Eckener’s insistence on safe, conservative flight practices. This prudent, safety-minded approach grew out of direct personal experience. Although by 1936 he was widely considered to be one of the most gifted airship commanders in the world, Hugo Eckener’s flight career had begun on a decidedly ignominious note.

In 1911, after a decade of association with Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin and numerous flights aboard his airships, Eckener was given his very first command, the LZ 8 Deutschland II. It was a small passenger airship, primarily used for pleasure cruises lasting a couple of hours. On May 16, 1911, Eckener was preparing for his first flight as the ship’s commander. The Deutschland II was still in its hangar, and Eckener was concerned that the blustery wind conditions could cause major problems in undocking the airship. However, the passengers were already aboard and there were several very influential individuals among them. In addition, a large crowd of spectators had gathered near the hangar and everyone was clearly anxious for the flight to begin.

Dr. Hugo Eckener (at right, in dark cap with goggles) and Count von Zeppelin

Dr. Hugo Eckener (at right, in dark cap with goggles) and Count von Zeppelin

(left, in white cap) in the control gondola of the LZ 10 Schwaben in 1910.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

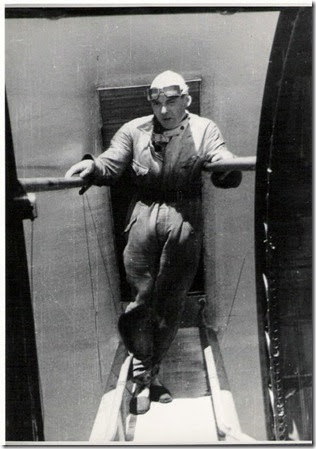

Dr. Eckener, noting the growing impatience of the passengers and the onlookers, went against his own better judgment and ordered the Deutschland II to be walked from her hangar. A large windscreen had been erected to one side of the hangar doors, designed to prevent a crosswind from sending the airship out of control while she was being undocked. Unfortunately, it didn’t work. As she cleared the hangar, a stiff wind caught the Deutschland II and drove her up and backward, dropping her bow onto the hangar roof and impaling her aft section on the very windscreen that had been meant to protect her. Amazingly, nobody was injured, and the passengers were all safely brought down from the ship via a large fire ladder.

descending the fire ladder below the row of observation windows along the airship’s keel.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Dr. Eckener, however, was chastened by what had happened. As he later wrote, “I paid for my weak-kneed decision by damaging the ship so badly that she had to be almost completely rebuilt, and thereafter was cured of such compulsive acts.” Never again would Eckener allow himself to be goaded into such a reckless decision in order to cater to public opinion or political pressure, and he drilled this same caution into the airship commanders he trained. The safety of the passengers and crew (and therefore, by extension, the airship) would henceforth be the first and most important consideration at all times.

By March of 1936, however, much had changed. Although he was on the DZR’s board of directors, Dr. Eckener no longer had much say over the flights of the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg. Captain Ernst Lehmann, the Hindenburg’s commander, was also Director of Flight Operations for the DZR. Unlike Eckener, who had little use for the new Nazi regime (and was not afraid to voice such opinions when the mood struck him), Ernst Lehmann was far more willing to curry favor with the Berlin government. Whether this was for practical reasons or because of an actual belief in Nazi ideals on Lehmann’s part is unknown. He was indeed an official member of the Nazi Party, but then again a number of his colleagues had also joined the Party, more for the good of their careers than for ideological reasons.

Since the DZR fell under the aegis of Hermann Goering’s Air Ministry, the Berlin government had the prerogative to use the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg as they saw fit. In this case, Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda ordered the four-day propaganda flight as a way of publicly legitimizing Hitler’s abrogation of key terms of the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties through his decision to send German troops into the Rheinland. In addition, the flight would also be the Berlin government’s first opportunity to show off the new Hindenburg, its tail fins emblazoned with 30-foot high scarlet, black and white swastika flags proclaiming the might of the Third Reich.

The flight was technically a charter, with the Air Ministry paying 88,900 Reichsmarks to the DZR for use of both airships for the four-day period. However, the flight would also come at a cost – one that barely registered to the government in Berlin, but which weighed heavily upon Dr. Eckener’s mind. In order to schedule the propaganda flight, it would be necessary to forego the Hindenburg’s final 12-hour full-speed engine trials. The airship was scheduled to depart on her first transoceanic flight, to Rio de Janeiro, early on the morning of March 31. With the propaganda flight lasting until the evening of March 29, there simply would not be time to prepare her for her South America flight and also to fly the 12-hour engine test flight.

Berlin had already asked Dr. Eckener to join other prominent Germans in going on the radio and publicly proclaiming his support for the Führer’s Rheinland policies. Eckener refused, of course. He had always refused the Nazis’ attempts to convince him to lend his approval to what he considered to be a culture of thuggish madness. In 1932 when the growing Nazi Party asked him to join them and requested his permission to allow them to use the giant Zeppelin hangar at Friedrichshafen to hold one of their rallies, Eckener turned them down flat. And in fact, shortly after refusing the Nazis’ requests, he had gone on the radio and made a nationwide address to garner public support for the policies of then-Chancellor Heinrich Brüning, leaving no doubt as to where his political sympathies lay. This led to a movement among the left-leaning Social Democratic Party and the German Centre Party to draft Eckener to run against Hitler in Germany’s 1932 presidential election in place of their aging candidate, incumbent President Paul von Hindenburg. Eckener, flattered though he was by the offer, declined, citing his preference to continue his life’s work with the Zeppelins.

President von Hindenburg won his re-election bid, and immediately appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor. Eckener, clearly disgusted by this turn of events, continued to turn down Nazi requests for his public support, which created more and more friction between himself and Nazi Party officials as their hold over the German government intensified. However, the order to fly the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg over Germany in support of those policies was something that Eckener was in no position to deny. His seat on the DZR’s board of directors was largely an honorary one, and the government now held partial ownership of the two Zeppelins. The propaganda flight would proceed as ordered.

Eckener also refused to take part in the flight itself. As he would later write, “Apart from my political convictions, I considered this misuse of the airships in bad taste, a sort of sacrilege, and I refused to participate myself.” To colleagues at the time, he was even more blunt in his assessment of the situation, saying, “If the airships are used for political purposes, it will be the end of the airship.”

Dr. Eckener, therefore, was not present at the Löwenthal airfield when the Hindenburg was brought out of her hangar on the morning of March 26, 1936. Aboard were 58 passengers, including representatives of both the Air Ministry and the Ministry of Propaganda, members of the Plebiscite Commission that would be managing the March 29 national vote, and reporters from the press and the radio. The Hindenburg’s control car had been equipped with a loudspeaker, from which martial music and electioneering messages encouraging Germans to vote “ja” on the upcoming referendum would be broadcast to the crowds below. Boxes full of political leaflets and small parachutes with tiny swastika flags had been stowed in one of the airship’s freight rooms to be dropped during the flight.

One of the pamphlets dropped from the Graf Zeppelin and

One of the pamphlets dropped from the Graf Zeppelin and

Hindenburg during their four-day propaganda flight.

Departure had already been delayed for two hours due to a gusty northeast wind of 6-8 knots complicating the undocking of the Hindenburg, which was in her hangar facing due west. Captain Lehmann, however, was anxious to get started. There was a large crowd onhand at the airfield to watch the new ship take off, including a number of important government dignitaries for whom Lehmann wanted to put on a good show – shades of Dr. Eckener’s experience with the Deutschland II twenty-five years earlier.

Among the crowd of onlookers were two Americans. Lt. Commander Scott E. “Scotty” Peck had been sent to Germany by the US Navy to observe the new Zeppelin and to take part in her test flights. This had been arranged by Dr. Eckener and Admiral Ernest King, Chief of the US Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics, and Peck had been in Germany since mid-February. He had originally been scheduled to fly aboard the Hindenburg for the propaganda flight, but had been informed the previous evening by Captain Lehmann that word had come from Berlin that Peck, as a foreign national, would not be allowed to make the flight.

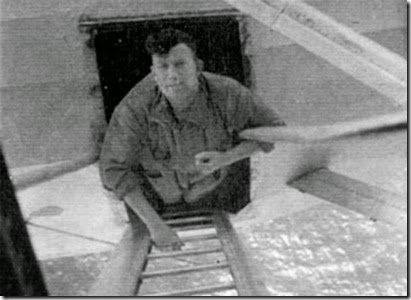

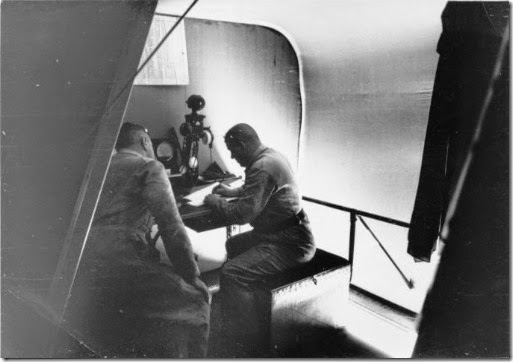

Scotty Peck (left) and Ernst Lehmann in the control car of the Hindenburg,

Scotty Peck (left) and Ernst Lehmann in the control car of the Hindenburg,

following her first transatlantic flight to the United States, May 9, 1936.

Another who had also planned to participate in the flight, but who now watched the proceedings from the ground due to the edict from Berlin, was Harold G. “Hal” Dick. Dick, a skilled engineer as well as a licensed pilot, had been in Friedrichshafen as a technical observer since 1934 via an arrangement between the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin and his employer, the Goodyear-Zeppelin Company in Akron, OH. He had flown numerous times on the Graf Zeppelin, and on the Hindenburg’s early test flights, often standing watches in the control car along with the regular crew.

A close friend of Dr. Eckener and his son, Knut Eckener, Hal Dick’s presence at the Friedrichshafen airship works continued to be tolerated by the Berlin government even after the nationalization of flight operations in 1935, due to Dick’s having been at the Luftschiffbau for so long that they considered him to be, as Dr. Eckener put it, “like an old piece of furniture.” However, Berlin’s courtesies did not extend to this propaganda flight, and Dick had also been informed that he would have to sit this flight out.

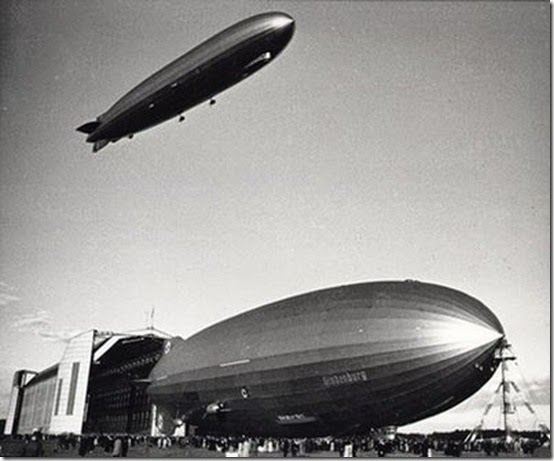

The Graf Zeppelin circles overhead as the Hindenburg is removed from her mooring mast.

The Graf Zeppelin circles overhead as the Hindenburg is removed from her mooring mast.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

The Graf Zeppelin, meanwhile was already in the air and circling the Löwenthal field. She had been berthed at the airfield at Friedrichshafen a few miles away, and her commander, Hans von Schiller, had not had any trouble bringing the Graf out of her hangar, which was oriented in a more favorable direction in relation to that morning’s northeast wind. Lehmann decided that, given the fact that the wind was coming from almost directly aft of the Hindenburg, the airship would make a downwind takeoff.

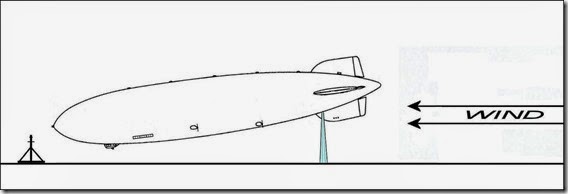

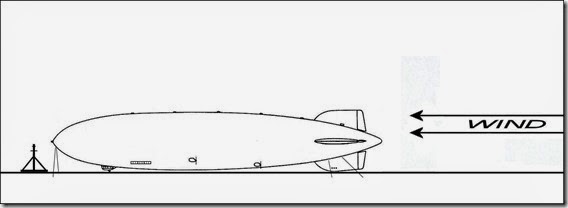

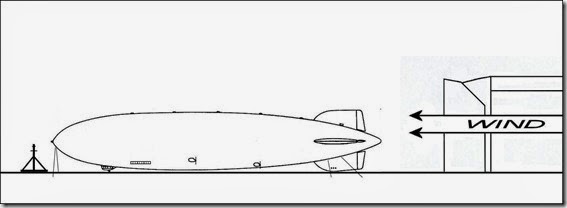

Normally, a Zeppelin took off with its bow into the wind, so as to immediately catch the wind with its aft control surfaces and generate aerodynamic lift. A downwind takeoff was more difficult, riskier and considerably less than ideal. In this case, the ship’s stern, rather than its bow, would be pointed into the wind:

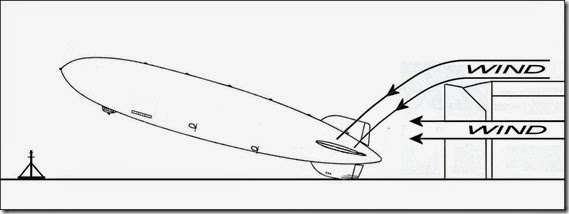

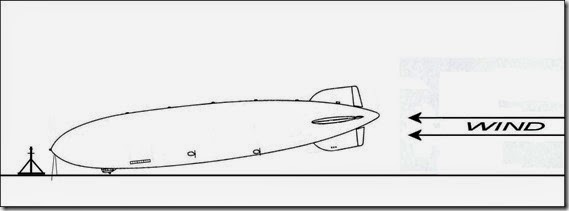

The aft mooring ropes would be cast off and her tail pushed into the air while the nose remained held down by the ground crew. This was to allow the wind to get up under the tail fins in order to generate lift and forward speed:

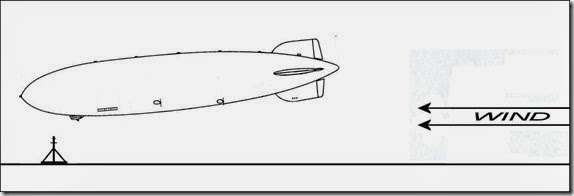

Once the tail had risen approximately 30 or 40 feet (10-12 meters) into the air, the bow would be released and the ship allowed to move forward with the wind, gaining altitude through a combination of her own lift and the force of the wind:

What made this maneuver tricky was the fact that once the airship’s bow was released, it would tend to rise, encouraging the ship to pivot on her center of gravity and push the ship’s tail down. Water ballast would therefore be dropped from the aft end of the ship in order to keep the tail up until the ship was underway.

However, despite the risks of such a takeoff, Ernst Lehmann had decades of experience flying Zeppelins under all weather conditions, and he had made many successful downwind takeoffs before. There was no reason to believe that this time would be any different.

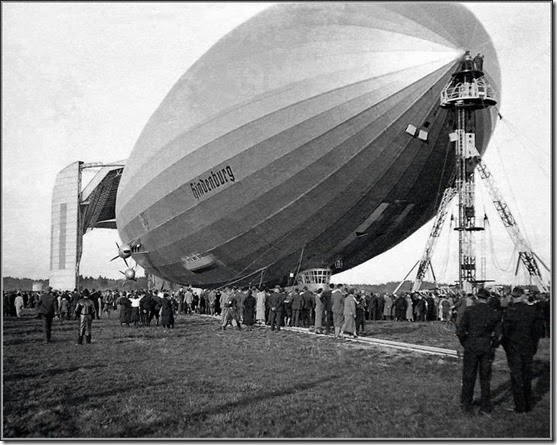

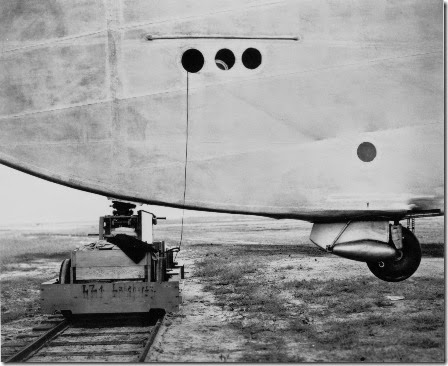

Just before 6:00 AM, Lehmann ordered the ground crew to walk the Hindenburg out of her shed, her nose cone still held by the mobile mooring mast and her aft section held by landing ropes attached to trolleys running along rails to port and starboard.

One of the docking rail trolleys can be seen at lower left as members of the

One of the docking rail trolleys can be seen at lower left as members of the

ground crew bring the Hindenburg out of her hangar on an earlier test flight.

As her bow emerged, the assembled crowd saw, for the first time, the red gothic lettering bearing her name along the side of her hull, above and slightly forward of the control car. Designed by Georg Wagner of Berlin, the lettering had been applied to the Hindenburg following her 6th trial flight a few days before. It had not gone unnoticed that the first half-dozen flights had been carried out without the ship bearing her name – long considered an ill omen among mariners.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

The Hindenburg, her name freshly painted on her hull, is led from her hangar on March 26, 1936

The Hindenburg, her name freshly painted on her hull, is led from her hangar on March 26, 1936

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Once the Hindenburg was clear of the hangar doors, Lehmann ordered the ground crew to uncouple the portside ropes from trolleys and to haul her bow to port, so that the ship would be oriented with her stern into the northeast wind. As the ground crew pulled the ship into position, one of the starboard ropes snapped loose from its trolley, and according to witnesses “the ship began to walk the men across the field instead of the men walking the ship.”

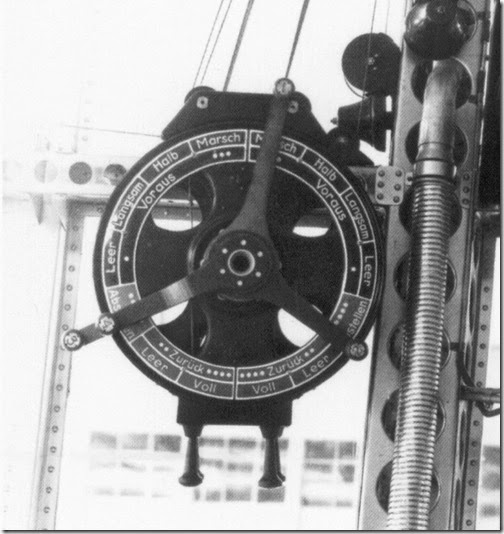

Lehmann, seeing this, gave the order, “Up ship! Stern first!” The ground crew released the Hindenburg’s tail, which ascended before the wind as planned. In the control car, the man at the elevator wheel (later identified by Harold Dick as senior rudderman Kurt Schönherr – though it is unknown why Captain Lehmann would have put a rudderman on the elevators for such a delicate takeoff maneuver) kept the horizontal control surfaces in the “up” position so as to allow the wind to more easily get under the fins and lift the tail.

Once the ship’s stern had risen about 30 feet into the air, Lehmann ordered the bow to be released.

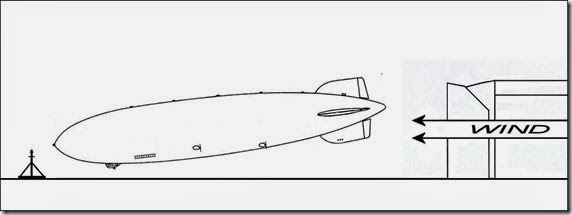

And then, inexplicably, Captain Lehmann ordered water ballast to be dropped from the bow. This was, of course, the exact opposite of what the downwind takeoff procedure called for, and it had the expected effect.

With the bow now lightened and rising fast, the tail began to drop. The horizontal tail fins, which had been aligned to catch the wind underneath them, suddenly began catching the prevailing wind on their topside surfaces.

To make matters worse, there was also wind spilling downward onto the horizontal fins from the top of the hangar, which was still a relatively short distance aft of the ship. This hit the control surfaces, pushing them downward with enough force to rip the wheel out of the elevatorman’s hands and send him sprawling across the control car. Furthermore, the control chains attached to the elevator wheel were brought up against their stops so sharply that they snapped.

By now, the Hindenburg’s bow had risen high into the air (Lt. Commander Peck estimated that her nose was up by approximately 15 degrees) and the stern had seesawed down far enough to slam the rear of the lower tail fin into the ground, crumpling the aft-most third of the fin’s lower edge and damaging the rudder. Lehmann immediately ordered multiple ballast drops to lighten the ship and get her airborne. With the lower rudder damaged and the elevators temporarily out of commission, the Hindenburg rose into the air and then free-ballooned over the town of Friedrichshafen and out over Lake Constance.

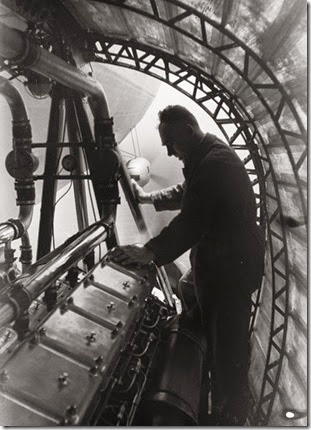

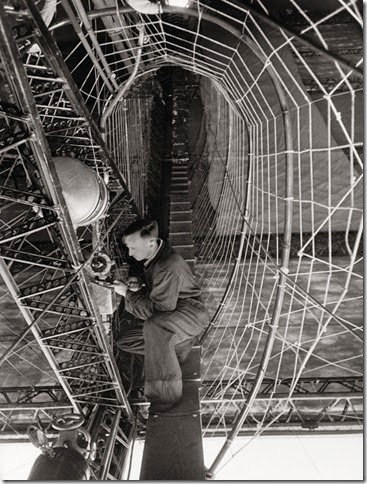

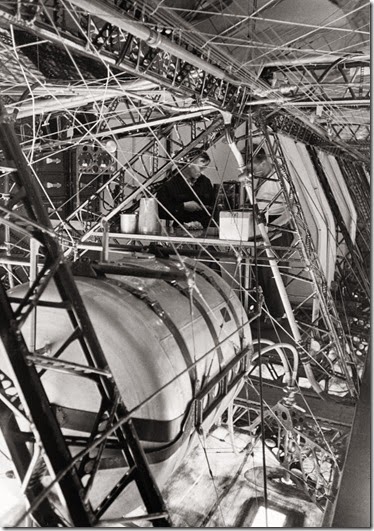

Lehmann immediately ordered elevator control transferred to the emergency control stand in the forward part of the lower tail fin. The lower rudder cables were also unshipped from the rudder wheel, leaving only the upper rudder for lateral control. The Hindenburg cruised over the lake for an hour or so as the riggers and flight engineers made a thorough internal inspection of the aft portion of the ship in order to determine the extent of the damage. As it turned out, the damage seemed to be confined to the impact area.

The wind that had plagued the Löwenthal airfield died down to a couple of knots by mid-morning, and Captain Lehmann brought the Hindenburg in to land. As she was walked back to her hangar, people in the crowd began snapping photos of her damaged tail fin. Security officers and DZR personnel quickly swept through the crowd, grabbing cameras and yanking the film out. A few quick-thinking individuals – including Hal Dick, whose photos appear here – managed to hide their cameras and preserve their photos of the Hindenburg’s crumpled fin.

Wichita State University Libraries)

Meanwhile, as Lehmann climbed down from the control car to survey the damage, a furious Dr. Eckener stormed up to him and let him have it, in full earshot of the crowd of onlookers. Their new airship had come perilously close to being wrecked, and Eckener was in no mood to mince words.

“How could you, Herr Lehmann, order the ship to be brought out under these wind conditions?!” Eckener bellowed. “You had the best excuse in the world to postpone this Scheissfahrt [literally, “shit flight”], but instead you risk the ship merely to avoid annoying Herr Goebbels! Do you call this showing a sense of responsibility toward our enterprise?!”

Lehmann reminded Eckener that he was under direct orders from the government to make the flight, and had little choice but to carry out those orders.

Eckener turned and regarded the damaged airship. “What do you want to do with it?” he asked.

Lehmann replied that he could have temporary repairs made within a couple of hours and get the Hindenburg back into the air to join the Graf Zeppelin. This infuriated Eckener even further.

"So this is your only concern?! To take off quickly on this mad flight and drop pamphlets for Dr. Goebbels?! The fact that we have to take off for Rio in four days and have made no flights to test the engines apparently means nothing to you!"

Lehmann, unshaken (outwardly, at least) by Dr. Eckener’s rebukes, ordered the Hindenburg to be returned to her hangar for repairs. Fortunately, the damage was relatively minor. A 6-foot section at the bottom of the lower rudder had broken off and hung loose by a few girders, and a 10- to 15-foot span of the fin’s lower edge was smashed and bent.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

The damaged section of the rudder was removed and the crushed area along the edge of the lower fin was faired in. After cutting away the bent girders and replacing the outer cover, Luftschiffbau workers had the Hindenburg ready to go once again within two hours, at about noon.

(photo courtesy of Courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives,

(photo courtesy of Courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives,

Wichita State University Libraries)

Meanwhile, the wind had shifted from northeast to northwest, picking up again to about 6-8 knots. Unfortunately, the Hindenburg had been returned to her hangar in the opposite direction she had been earlier in the morning, and so Lehmann was faced with almost identical wind conditions when it was time to take off again. He waited until 3:00 that afternoon for the wind to die down, which it eventually did somewhat. Once more, the Hindenburg was walked from its hangar onto the airfield, this time with a conspicuous “bite” out of its lower tail fin.

(photo courtesy of Courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives,

(photo courtesy of Courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives,

Wichita State University Libraries)

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Two views of the Hindenburg being brought out onto the airfield after her repairs.

The Graf Zeppelin, which had been in the air since early morning, flies overhead.

As a matter of expediency, or perhaps even somewhat out of a need to prove his skills as an airshipman after the morning’s fiasco, Lehmann decided to proceed with another downwind takeoff. This time, Dr. Eckener was present on the airfield, standing with the ground crew beneath the Hindenburg’s tail, which was released and rose to a height of about 30 feet. Then, the forward ground crew pushed the bow into the air. Dr. Eckener watched incredulously as Lehmann once again dropped water ballast in two streams from the Hindenburg’s bow. The stern began dropping, and one of the ground crewmen standing near Dr. Eckener exclaimed, “It’s coming back down again, just like this morning!”

Fortunately, with the wind not being quite as strong as it had been that morning, Lehmann had time to order ballast dropped from the stern of the ship in time to check its descent. The Hindenburg now rose into the air, although according to Lt. Commander Scott Peck, the ship was now visibly and badly out of trim after throwing out so much ballast. Once the engines had been started, however, and the ship had forward speed, her elevatorman was able to hold the Hindenburg on an even keel as the engineering crew redistributed fuel and water along the keel to bring the ship back into balance. The Hindenburg now, at last, joined the Graf Zeppelin (still circling overhead) and the two ships proceeded with their four-day tour of Germany, flying over every town with a population greater than 100,000.

reams of leaflets from open portholes in the airship’s lower tail fin.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

The next day, Dr. Eckener drafted a letter which he subsequently distributed to each of his captains. In it, he recounted the events of the previous day, including both the morning’s botched downwind takeoff and the near-miss that had occurred in the afternoon. Captain Lehmann, who was writing his autobiography at the time, would dismiss the incident in that volume as being “meaningless in itself,” describing it thusly: “The unpracticed ground crew tore one of the steel spiders which held the stern of the ship and a gust of wind, blowing at a thirty-five degree angle to the hangar, pushed the stern fins to the earth and bent them.” It is entirely possible that Lehmann had attempted to shift blame to the ground crew in a similar fashion during his confrontation with Dr. Eckener on the airfield at Löwenthal, as Eckener made a point of prefacing his examination of the incident in his letter by stating, “I do not wish to examine whether or not the ground crew behaved incorrectly (which, by the way, I doubt.)”

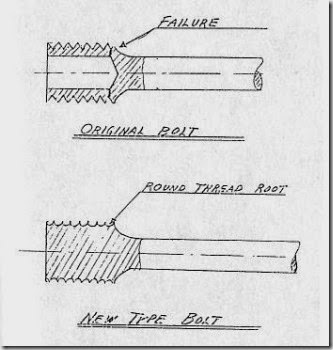

In the letter, Eckener also outlined the precise procedures that were to be observed and followed for any downwind takeoffs from that point forward (and which form the basis for the first set of diagrams shown above.) Though he had no official control over the actions of the DZR command crews, the crew members themselves had long served under Eckener’s command and were well acquainted with his prodigious expertise when it came to piloting. Especially given the operational near-disaster that the Hindenburg had just experienced, the DZR’s commanders and watch officers would almost certainly take heed of “The Old Man’s” words on the matter.

In Berlin, however, Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels had been informed of “The Old Man’s words” to Captain Lehmann after the Hindenburg had landed for repairs. There were, of course, representatives of the Ministry onhand, both as passengers and as spectators on the ground, and it did not take long for Dr. Eckener’s enraged outburst to be relayed back up the chain of command. Goebbels responded swiftly by essentially declaring Eckener to be, for all intents and purposes, a non-person. At a press conference less than a week later, as the Hindenburg, with Eckener aboard, was making her first flight to South America, Goebbels issued the following proclamation to members of the press:

“Dr. Eckener has alienated himself from the nation. In the future, his name may no longer be mentioned in the newspapers, nor may his picture be further used.”

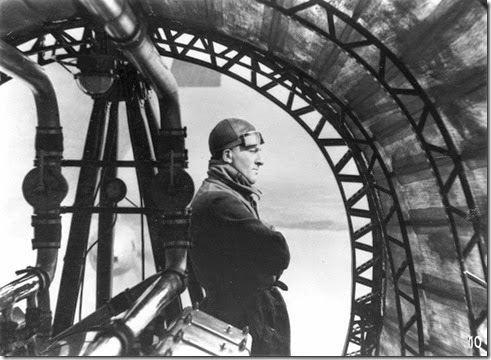

Upon his return from South America the following week, Eckener met with Air Minister Goering and managed to get the whole mess straightened out. He explained to Goering that his primary concern, and the main reason for his having taken Captain Lehmann to task and disparaging the propaganda flight the way he did was the fact that vital engine tests had to be canceled in favor of the electioneering charter, and that they would have to take the Hindenburg across the Atlantic for the first time without having given her engines their necessary 12-hour full-speed trials. And, as it turned out, the Hindenburg experienced multiple engine breakdowns during the South America flight that may well have been prevented had the airship been able to complete her full battery of test flights. At the end of the return leg of the voyage, Eckener had brought the Hindenburg back to Friedrichshafen on two of her four engines, with a third operating at half speed.

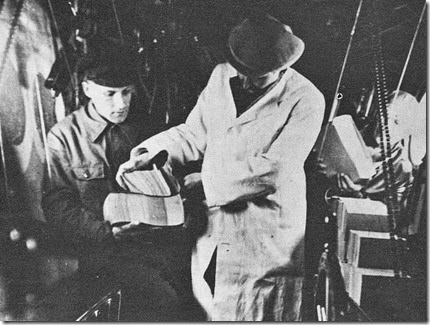

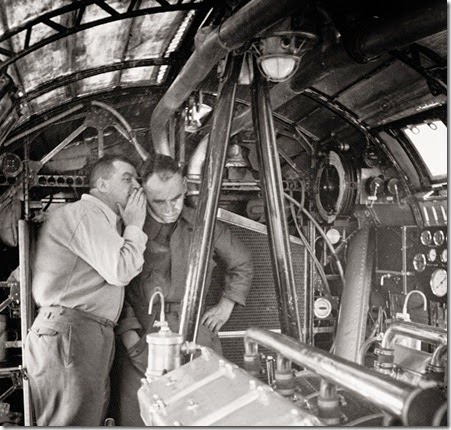

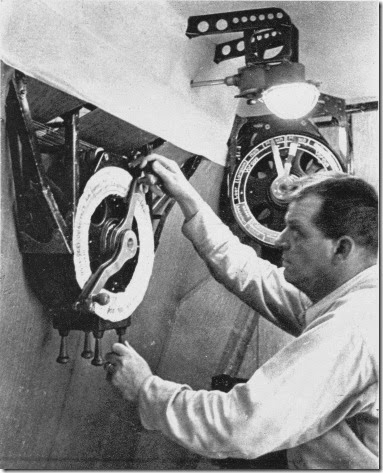

Flight Engineer Raphael Schädler examines the LOF-6

Flight Engineer Raphael Schädler examines the LOF-6

diesel in engine car #4 during the Hindenburg’s first

flight to South America. This was one of the engines

that experienced problems during the voyage.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Air Minister Goering had never been a fan of the Zeppelin concept, often privately dismissing them as “Dr. Eckener’s gas bags.” Nevertheless, as an experienced pilot and decorated WWI fighter ace, he could not deny the fact that Eckener’s operational concerns had been valid. However, during their meeting he focused largely on the perception in Berlin that Eckener had a history of disrespect toward Hitler and his government. There was Eckener’s repeated refusal to publicly support the Nazi Party, as well as his penchant for outspoken public statements that made light of the government. Goering referred specifically to an occasion when, asked by a foreign journalist why he did not use the de rigueur “Heil Hitler!” greeting, Eckener had responded, “When I get up in the morning, I don’t say ‘Heil Hitler!’ to my wife, but rather, ‘Good morning.’ “

According to Eckener’s later memoir, Goering seemed to come to the heart of the matter, however, when he remarked to Eckener, “They say you would have liked to have succeeded von Hindenburg as president.” Eckener assured Goering that the notion had come from others and not himself, and that he had never entertained thoughts of leaving his life’s work behind for a career in politics. Whether or not Goering was truly convinced of Eckener’s sincerity, he did pull the necessary strings to get the press ban lifted and to have Eckener’s name cleared.

The Hindenburg would receive more extensive repairs to her lower tail fin following her return to Germany from her maiden transatlantic voyage to South America. An overhaul of all four of her diesel engines to correct the problems that arose during the flight to Rio would require the airship to be laid up in her hangar for at least a couple of weeks. This gave Luftschiffbau construction crews time to rework the damaged section of the fin, permanently fairing it in so that the lower edge curved up from the forward-most point of the damaged section to the bottom edge of a slightly shortened lower rudder.

The Hindenburg’s original lower fin configuration prior to the March 26, 1936 incident.

The Hindenburg’s original lower fin configuration prior to the March 26, 1936 incident.

Note the straight line along the lower edge of the fin, continuing out to the aft edge of the rudder.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

The Hindenburg with her reworked tail fin. Note the slight upward curve to the fin’s lower edge that

cuts off the lower aft corner of the red field of the flag, as well as the curved lower edge of the rudder.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Meanwhile, the public referendum vote on the Rheinland issue had gone as Berlin had planned. Aboard the Hindenburg itself, on the final day of the flight, 104 “ja” ballots were cast by 104 passengers and crew – though scuttlebutt among the crew was that there had actually been two “nein” votes that onboard election officials had secretly changed to “ja” votes to avoid  embarrassment for the Zeppelin company. Throughout Germany, 99% of the people reportedly voted in favor of Hitler’s remilitarization of the Rheinland, although it is likely that the near-unanimous vote totals as reported by official sources were deliberately inflated by Plebiscite Commission members in order to create the illusion of stronger public support of the Third Reich’s policies. The Rheinland, which the Germans had retaken without a shot being fired, was only the first of many military incursions by the Reich into neighboring lands, and the first step along the road that would lead Europe back to war.

embarrassment for the Zeppelin company. Throughout Germany, 99% of the people reportedly voted in favor of Hitler’s remilitarization of the Rheinland, although it is likely that the near-unanimous vote totals as reported by official sources were deliberately inflated by Plebiscite Commission members in order to create the illusion of stronger public support of the Third Reich’s policies. The Rheinland, which the Germans had retaken without a shot being fired, was only the first of many military incursions by the Reich into neighboring lands, and the first step along the road that would lead Europe back to war.

Special thanks to Dennis Kromm for his generosity in providing me with his rough sketches that I used to create the diagrams presented here, illustrating the downwind takeoff – both the proper procedure, and the procedure that Captain Lehmann followed on March 26, 1936.

Dennis was also kind enough to provide a copy of the letter from Dr. Eckener to his captains, dated March 27, 1936, in which he outlines the correct procedure for a downwind takeoff in response to the previous day’s mishap. Dennis also shared with me his own written notes on the incident as well as the official USN report on the incident that Lt. Cmdr. Scott Peck submitted to Admiral King at the Bureau of Aeronautics.

The Eckener letter itself comes courtesy of Cheryl Ganz, whose late husband, Felix Ganz, translated the letter into English.

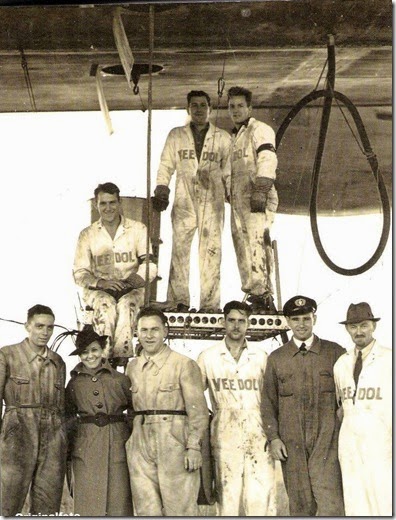

Leaning into the 80 MPH slipstream, an engine mechanic (probably

Leaning into the 80 MPH slipstream, an engine mechanic (probably

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiFakQQzPhrjfNIKnNu7TQ4POGsPprXi5zp7fiVGSkWvcXEb6ejLSJ57EpYoPrkSlkldKgMgQycZI9ZlYUNdbMJpT8Y8czAITOmH6KaPLWyEFImixq3pt4sWFV2e1N7DwNF_PXHDmQYm0s/?imgmax=800)